Sophronia Cook: Limbo

May 2 - June 8

Opening Reception: May 2nd, 6 - 9 PM

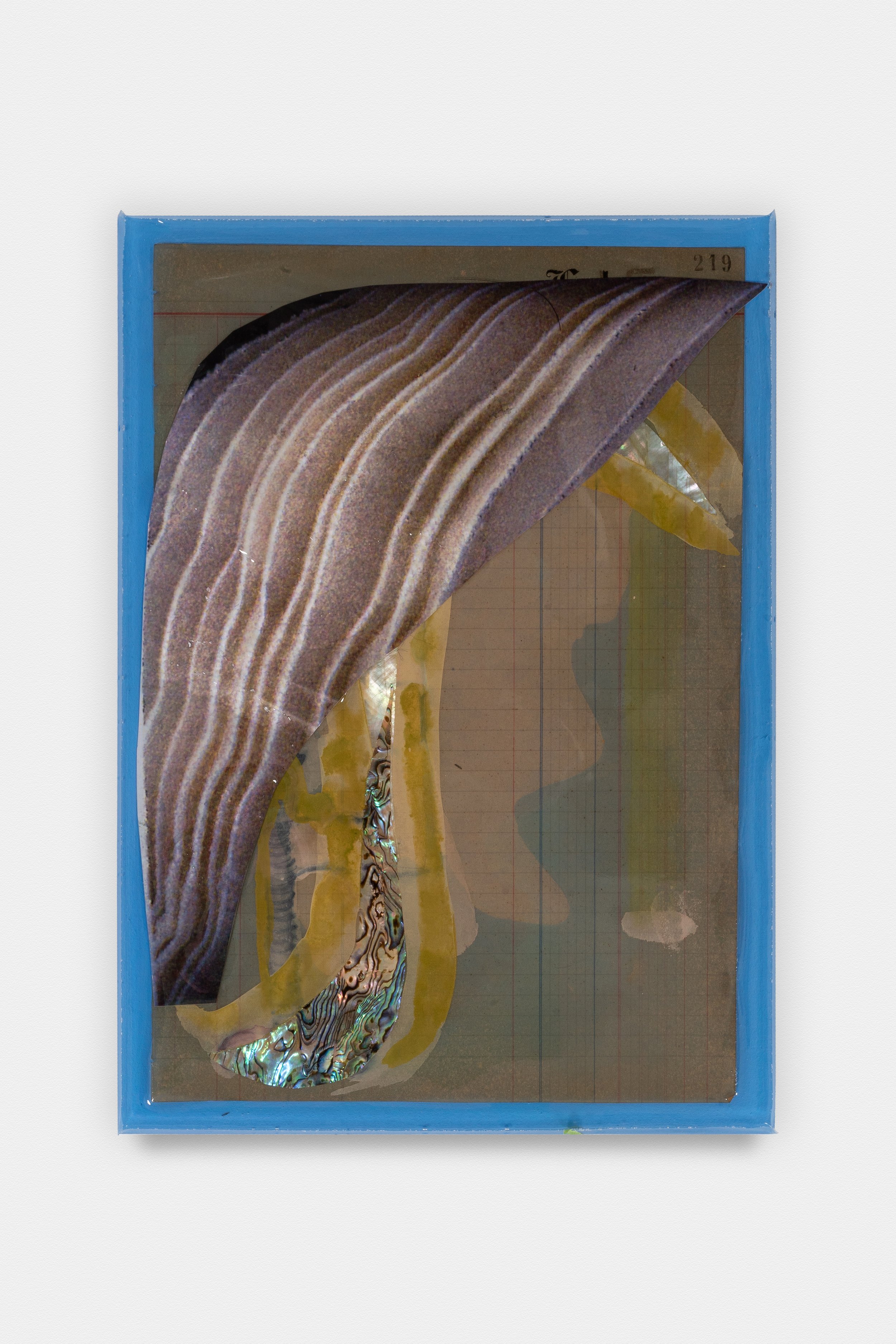

Between texture and animal, a hungover carcass is grasping for revertive memories. The bones are gone, the formaldehyde has set in, the vivisection is complete and an alligator’s body is becoming all surface. A surface is a charged space.

In Anne Carson’s translation of Antigone, Antigonick, her lead says: “I’m a strange kind of in between thing, aren’t I,” after resigning herself to the condition of being buried alive. Not yet dead, but without the context of living — suspended in the subterranean, she’s becoming indistinguishable, becoming floor and wall and ceiling. In Brecht’s Antigone, a front door was bound to the imprisoned actress’ bent-over back.

In Sophronia Cook’s Limbo the half-life of an alligator is cast in severed discontinuities — frames of animal suspended. There’s a creeping luxury assigned to all this dead placidity. But, it doesn’t feel like taxidermy, it’s closer to the assembly of pool toys made to look like disembowled duckies. The synthetic is bruising, almost remembering how to bleed.

The heavy use of a synthetic turquoise is off-set by Cook’s painted figurations: often opalescent and amoebic, vaguely biological.

Beneath an alligator’s flattened form, splayed out and unspooling cast snail shells cling to the skin — remainders of life. My mind flashes to Lenin’s corpse. His body was preserved only after a week of open-air decay, so it’s held forever in a state of partial decomposition. The snail shells are interesting.

Madeline Gins and her husband Shūsaku Arakawa were fascinated with snails, as they represent a kind of being in which consciousness is irreducible from its physicality. A body that is also a formal shelter. A formal shelter that is all feeling, resounding with sensation.

I once chewed through my own lower lip in a state of ecstatic indulgence, biting through a kind of resolve, marking my pleasure with attempts at restraint. I spent the next few days smearing vaseline to embalm the wound and speaking slowly, with a lisp, marveling at how my body had cannibalized itself in a subconscious attempt at transcendence.

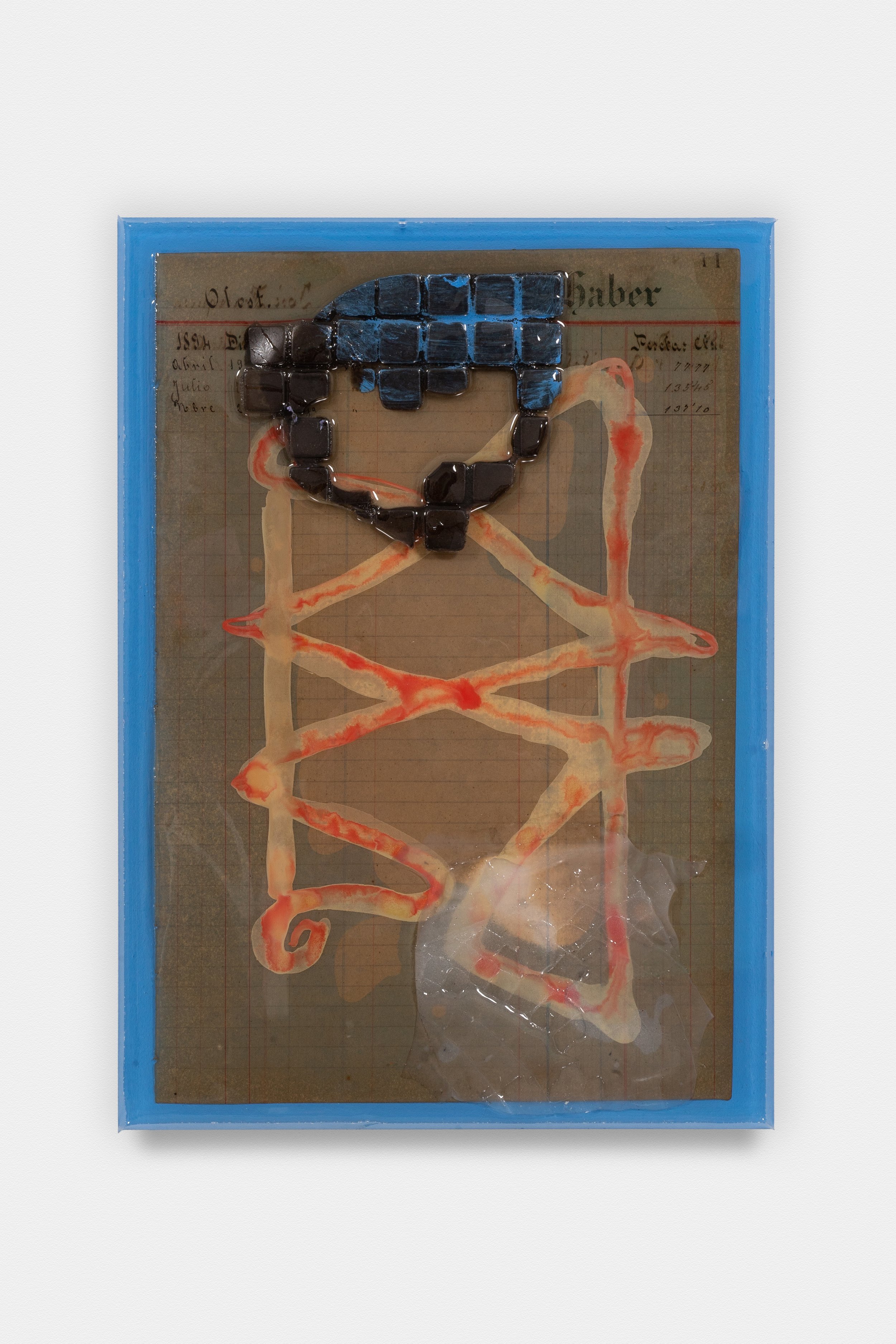

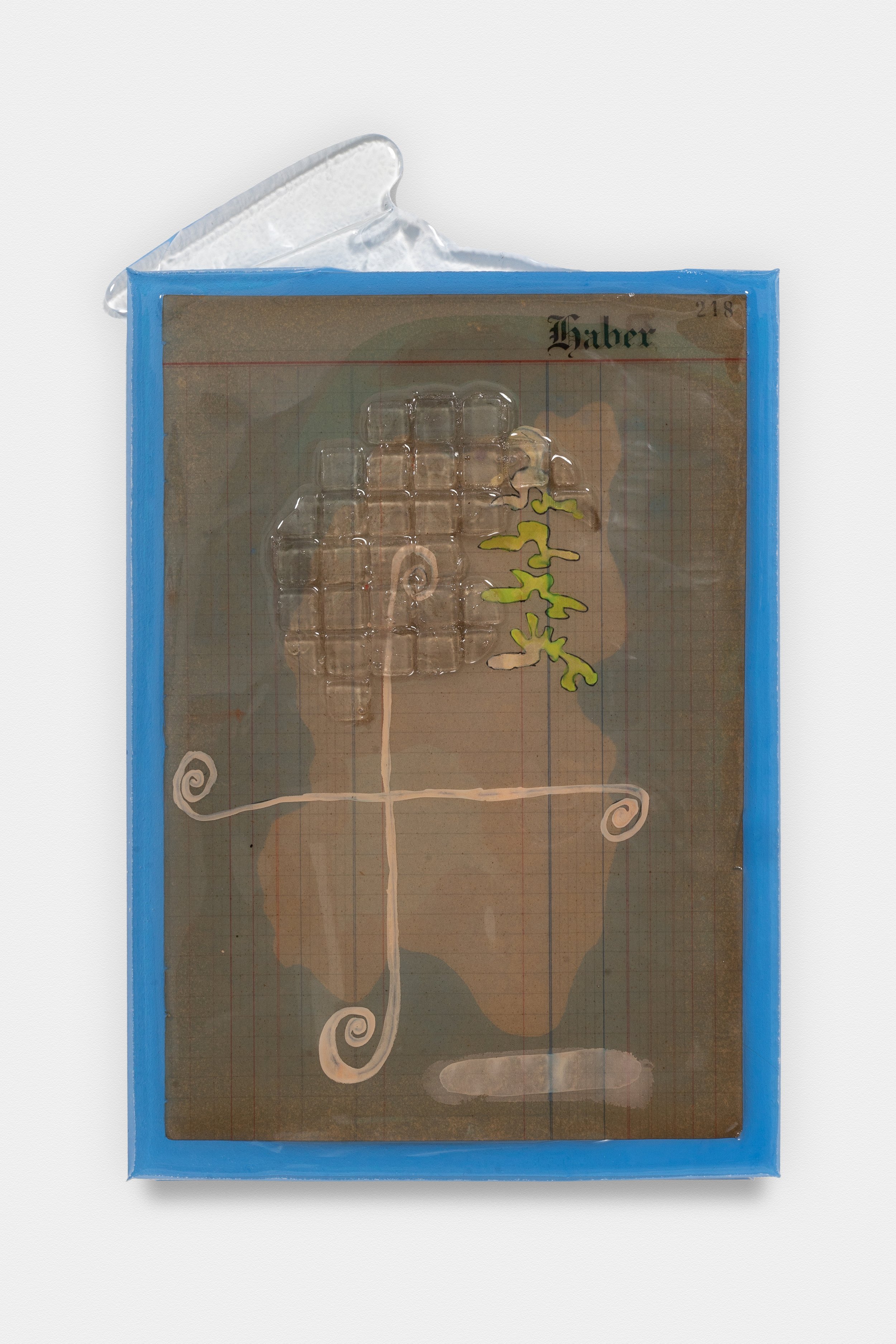

Works on drowned ledger papers, water-marked and hued by age, accompany the alligator pieces, many approximating its form with shadows of its gridded back. I read somewhere that every act of recollection disturbs the original memory. The image you imagine dislodges its predecessor, becoming ever-more blurred and imprecise. Visual memory then, is a bricolage re made again, and again, by context.

Text by Theadora Walsh

WORKS